The EU’s Digital Services Act Will Likely Establish New Global Standard

Updated

The European Union’s Digital Services Act (DSA) went into effect on November 16, 2022, profoundly impacting how every search engine, social network, and online marketplace operates in the EU. Ultimately, the new rules and regulations will likely establish a new global standard in platform governance for how digital services—the intermediaries connecting consumers with content, goods, and services—are controlled. With stringent, far-reaching, and somewhat vague obligations, the DSA forces the largest internet platforms to take prompt action against illegal and harmful content or face severe fines and remedies. No longer will tech giants be able to regulate themselves.

The European Commission (EC) states that the new rules and regulations outlined in the DSA aim to better educate and empower users to ensure a safe and accountable online environment, while facilitating the scaling up of smaller platforms and restraining the power of large ones like Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook (Meta). According to the nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), the DSA avoids transforming social networks and search engines into censorship tools and supports online expression, which “is great news.” Still, the group insists the DSA, with a great deal of ambiguity, “gives way too much power to government agencies to flag and remove potentially illegal content and to uncover data about anonymous speakers.”

The DSA complements the Digital Markets Act (DMA), which entered into force on November 1, 2022. The DSA creates responsibilities for online platforms to moderate content and enforce transparency in data collection, while the DMA is an anti-competition law targeting “gatekeeper platforms,” including Google, Apple, Amazon, and Facebook. The DMA requires gatekeepers (defined as platforms with “a systemic role in the internal market that function as bottlenecks between businesses and consumers for important digital services”) to obtain consent before using personal data for targeted advertising. The DMA and DSA function together to control digital services in the EU along with existing laws regulating online terrorist content, political advertising, and child sexual abuse material. The DSA and DMA have overlapping consent requirements with the General Data Regulation Protection Regulation (GDPR), and the majority of the gatekeeper companies targeted by the two Acts are located in the U.S.

Brief Overview of What’s New in the DSA

Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) & Risk Assessment

The over 300-page DSA requires online intermediaries to amend their terms of service, better handle complaints, and increase their transparency, especially regarding advertising. It also details the responsibilities of the EU member states when it comes to enforcement, pointing out that very large online platforms (VLOPs) pose the greatest risks—including risks to public health, civic discourse, elections, and gender-based violence. Thus, platforms with over 45 million users in the EU must formally evaluate how their products, including algorithms, may worsen these risks and then take action to discourage them. VLOPs must allow their internal data to be inspected by the EU and Member States as well as independent auditors, academia researchers and others in order to identify systemic risks and ensure that platforms control them. The EC and national authorities will have new, but somewhat unclear, enforcement powers over the largest platforms and search engines, with the authority to impose fines up to 6 percent of their global turnover as well as “supervisory fees” to help pay for tasks related to their enforcement.

Targeted Ads and Ad Transparency

This unprecedented new standard of DSA rules means platforms must clearly explain to users how their content moderation and algorithms work in a user-friendly language. Platforms must also give users the option to select a content curation algorithm that is not based on profiling. They must provide detailed information about why users were targeted with ads and explain to them how to adjust ad targeting parameters. To promote advertising transparency, platforms must, among a list of other mandatory criteria, explain whether ads are intended to target particular groups and, if so, provide the main parameters used for that purpose, including, when applicable, the main parameters used to exclude other groups at the same time.

Content Monitoring & Illegal Content

While preserving an EU-wide ban on general content monitoring, the DSA specifies clear rules to address illegal content, instructing platforms to act promptly to delete such content, with stiff penalties for failing to do so. Nevertheless, combined with the existing ban, under the DSA, platforms won’t be pushed to regularly police their platforms to the detriment of free speech. Still, EFF points out that the new rules could encourage platforms to over-remove content to avoid being held liable for it. The DSA also establishes new rights for users to challenge decisions on content moderation. Users must be given detailed explanations if their account is blocked or content is removed or demoted. Users can also contest these decisions with the platforms and, if necessary, seek out of court settlements.

Broad Reporting Requirements

The DSA spells out new broad transparency and reporting requirements, making it easy for law enforcement to uncover data about anonymous speakers. The DSA demands platforms produce annual content moderation reports that include details on any automated content moderation systems (Artificial Intelligence) used as well as a summary of their potential error rate and accuracy. Along with the volume count of and method used to handle user complaints, these reports must include the number of orders submitted (from “trusted flaggers” or Member States) to remove illegal content. Platforms are restricted from capitalizing on sensitive information, like race or sexual orientation, and ads can no longer target such data. Targeting data for minors is prohibited altogether. Manipulative interface designs, known as “dark patterns,” are also prohibited. More broadly, the DSA expands transparency about the ads users see on their feed, requiring platforms to place a clear label on all ads that provides information about the buyer of the ad and other details.

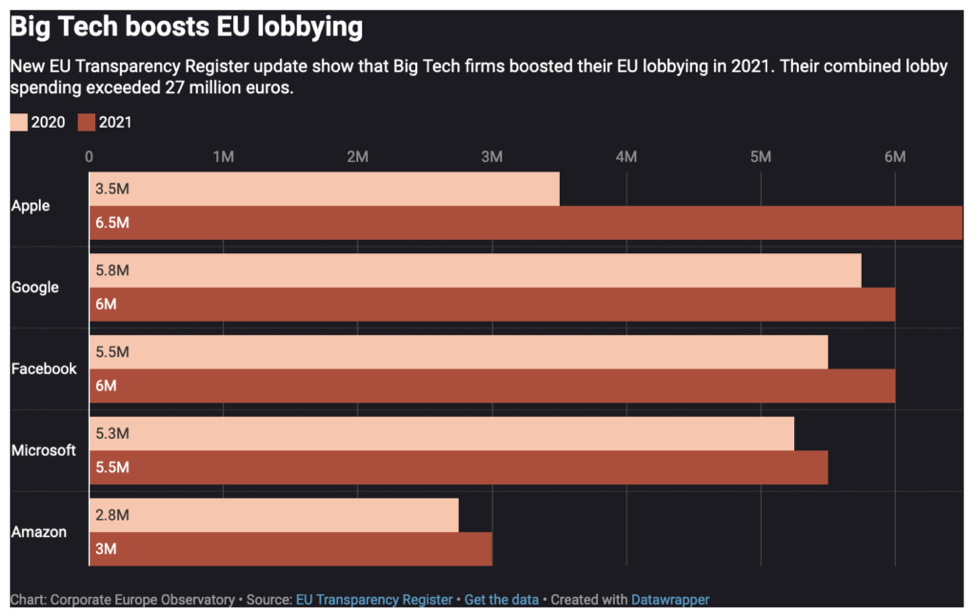

Big Tech’s Lobbying Efforts to Shape the New Tech Rules

Lobbying documents just released to Corporate Europe Observatory and Global Witness via freedom of information requests expose Big Tech’s intense last-ditch corporate lobbying to control the final stage of the EU policy-making process. Tech giants Google, Apple, Facebook, and others, in an attempt to neutralize the EU Parliament’s proposals to limit surveillance ads and expand external scrutiny of how the platforms’ systems amplify or demote content, jumped on the trilogues process (a type of meeting used in the European Union legislative process). They also sought to expand the companies’ future influence to sidestep market obligations like interoperability and access for smaller competitors. Corporate Europe Observatory remarked that this discovery confirms fears that trilogue secrecy only benefits wealthy and well-connected lobbyists.

According to Corporate Europe Observatory, who explains the underhanded efforts in great detail, the new lobby documents show that despite the trilogues process being one of the most secretive stages of EU policy-making, intense corporate lobbying happens regardless of the lack of transparency. Yet, EU institutions have insisted the secret process is required to prevent lobbying pressure on the policy-makers. Alongside European firms like Spotify and members of the copyright industry, Google, Apple, Amazon, and Facebook used the following tactics to influence the trilogues:

- pitting the EU Institutions against one another;

- becoming more technical and offering amendments to the text;

- using meetings to gain access to information that was not available to the public;

- going high level: bringing in the CEOs to meet Commissioners, inviting them to off-the-record dinners.

The DSA Looking Ahead

Online platforms have until February 17, 2023, to report to the EU Commission the number of active end users on their platform. The Commission will then evaluate which services meet the threshold (over 45 million active EU users) of being considered either a Very Large Online Platform (VLOP) or Very Large Online Search Engine (VLOSE), as noted by Algorithmwatch. The largest platforms and search engines will then have until June 2023 (four months) to comply with the rules in the DSA. Also by this deadline, they must have conducted and published their first annual risk assessments, as well as executed rules on content moderation. Likewise, users should begin to notice changes on the affected platforms. For example, the addition of a feature making it easy to flag illegal content, plus updated Terms and Conditions, which should be straightforward and understandable to all users, even minors.

On February 17, 2023, the DSA—which the WEF describes as part of a global effort “shaping the future of media, entertainment and sport”—becomes fully functional. By that time, each EU Member State must have assigned its own Digital Services Coordinator (DSC). As an independent regulator, the DSC will be responsible for executing the rules and regulations on smaller platforms in their countries, as well as aiding the Commission and other DSCs in more general enforcement efforts.

To help streamline the modifications that EU countries and the Commission must supervise to properly enforce the DSA, the Commission recently launched the European Centre for Algorithmic Transparency. European Commissioner Thierry Breton explained that starting in the summer of 2023, the Commission will thoroughly examine the compliance by large entities with the DSA. Currently working closely with U.S. Homeland Security Secretary Mayorkas on the EU/US cybersecurity dialogue, Breton tweeted in November, “Everyone is welcome to do business in the EU, but they will have to follow our rules.”

While unclear whether Twitter will meet the criteria for being classified as a VLOP in the EU, Elon Musk’s newly acquired platform, which has rightfully exposed egregious censorship efforts in the U.S., is clearly “the elephant in the room” as the DSA rolls out. Gerald de Graafe, the EU’s envoy for the DSA who is now firmly planted in Silicon Valley (along with others), has Twitter squarely on his radar. Previously, Musk has expressed support for the DSA to Thierry Breton, but de Graaf remarked that his office has been unable to reach him for a meeting. Speaking of Twitter in an interview with Foreign Policy, de Graaf commented, “You have a piece of legislation which will enter into force in the next six to eight months, and you see a very important company basically kind of decreasing quite significantly its capacity to moderate content.”

Next Stop, the United States?

While the DSA and DMA are both European laws, the fact the targeted gatekeeper companies are largely based in the U.S. is significant. Platforms that don’t comply can be hit with multiple violations at the same time. Time will tell whether the gatekeepers will choose to apply the EU privacy expectations to American users. However, as pointed out by Adexchanger, it’s likely they will eventually be forced to. For now, compliance with U.S. users is still their own decision to make.